An exclusive excerpt of Winter 8000: climbing the world’s highest mountains in the coldest season by Bernadette McDonald

What you are about to read is an exclusive extract from the book 'Winter 8000, Climbing the world's highest mountains in the coldest season' by Bernadette McDonald. To see more books we love and books that caught our eye, look at our book shelf - there's 10% off everything.

Partway down the ridge, at 4 p.m., Andrzej stopped to radio base camp with the news. ‘We have made the summit, made the summit, over . ’

Four p.m. is terribly late to be on or near a summit on 21 January. Only a month from the winter solstice, days are short. Within moments of calling base camp, darkness fell. ‘We did not have the faintest idea which way to go,’Jurek admitted.

Wandering in circles, they realised they were in danger of stumbling on to treacherously steep terrain. A bivouac in winter at over 8,000 metres was a terrifying prospect, almost sure to end badly. But they had no choice. They hollowed a small depression in the feather-light snow and sank down on to their packs. It was -40° Celsius. With nothing to eat or drink, they simply huddled together, struggling to stay awake.

Jurek occasionally slipped into a dreamlike state, only to wake with horror a few minutes later, convinced that hours had passed and he was frozen in place, dead. The night dragged on. They pummelled each other to keep blood moving to their extremities. They talked, offering encouragement and hope.

Down in base camp, Adam described the scene after having received their radio call. ‘For the next seventeen hours there was no other message. These hours seemed to be everlasting. That night a heavy storm was raging at the base and I didn’t know what was happening higher up. After twenty-five years I started to smoke again.

When the thin dawn light crept over the mountain, Jurek and Andrzej rose from their crouched position, unfolded their frozen arms and legs and began to move.

In half an hour they reached the tent. Andrzej turned on the radio. ‘Base camp. Base camp. We are at the tent. We are safe. We made the summit. Over.’

‘Great news. Congratulations. We were worried about you. What is your physical condition? Over.’

‘Okay. But I can feel nothing in my feet,’ Andrzej answered.

They spent the subsequent few hours dozing off, brewing tea and rubbing Andrzej’s horribly swollen feet. It was 2 p.m. before they left the tent, confident it would be a straightforward descent to Camp 2 or lower. It was essential that Andrzej reach base camp where he could receive some medical attention.

But they had miscalculated how tired they were. Their downward progress slowed to a crawl. Not even Camp 3 was now within reach.

Jurek slumped to the snow in near defeat. Andrzej continued ploughing down the slope, and since they weren’t roped together in this moderate terrain, they lost sight of each other.

Jurek raised his weary body, prepared to follow Andrzej, but the blowing snow had already buried his tracks. He panicked. He began to traverse off the ridge, could see nothing, reversed his steps and shouted. No response. Where was Andrzej? How could he have disappeared so completely? He must be in Camp 3. If so, it must be close. But where was it?

He kept plunging down the ridge, scanning ahead, peering left, struggling to spy some movement to the right, searching for Andrzej, desperate for a glimpse of Camp 3. When darkness fell, Jurek was still on the ridge, dropping blindly down.

That’s when he realised he would have to endure another bivouac, this one alone.

‘I wanted warmth. I wanted a drink. I was afraid that another night like the last could end in a drama, but what else remained?’

He scraped a small niche in the icy slope with his ice axe and opened his pack to retrieve his headlamp. It tumbled down the slope. ‘I sat down on my rucksack and the great battle for survival began all over again.’In that complete and utter darkness, time becomes elastic, one hour the same as one night or one day. Drifting in and out of consciousness, h3 became unaware of the wind tearing at his body.

Soon, the hallucinations began: Jurek is in a well-lit village at the foot of the mountain, eating and drinking, warm and safe. Now, he is transported to the Morskie Oko valley in the Polish Tatras, to his favourite mountain hut. Six friends at the table. Candlelight. Special mountain tea. Laughing, drinking, telling tales: some of them tall.

Late in the evening, they lower their voices. Someone asks,‘Have you touched the looking glass yet? Have you taken a peek?’

Some look confused, not understanding the question. But a few exchange knowing glances with Jurek before looking down. They have taken a look. So has Jurek. They know how it feels to approach the thin edge separating life from death. And they know they’ll go back. He pours another imaginary cup of tea, warming his cold hands. At dawn the next day, Jurek was still alive. When he staggered into Camp 2, he called out in a hoarse voice. Andrzej and the other climbers at the camp emerged from the tents, relieved to see him. Andrzej’s feet were in bad shape, but after arriving at 10 p.m., he had spent a warm night in his sleeping bag.

Now reunited, the climbers rested, drank some tea, packed up camp and prepared to head down to Camp 1. It would be a straightforward descent, since the wind had stopped and the sun was peeking through the clouds. Yet snow had drifted so heavily in the previous storm that they made little progress. Sliding and leaping from one drift to another, they were forced to bivouac one more time, the third night out in as many days for Jurek.

They finally reached the security and comfort of Camp 1 in the late afternoon of the following day – all except Jurek. Despite the agonies of three winter bivouacs in a row, he had other plans. Instead of going down to base camp and walking out with the rest of the team, Jurek had struck off for the French Col and the shortest possible route back to Marpha.

Since it had been snowing continuously for the past few weeks, he was soon immersed in chest-deep drifts. Acutely aware of the passing time, he pushed on, flailing in the deep snow, burrowing to create a tunnel through which he could make some progress. It was a mindless wretched fight, which at times brought him to the edge of tears.

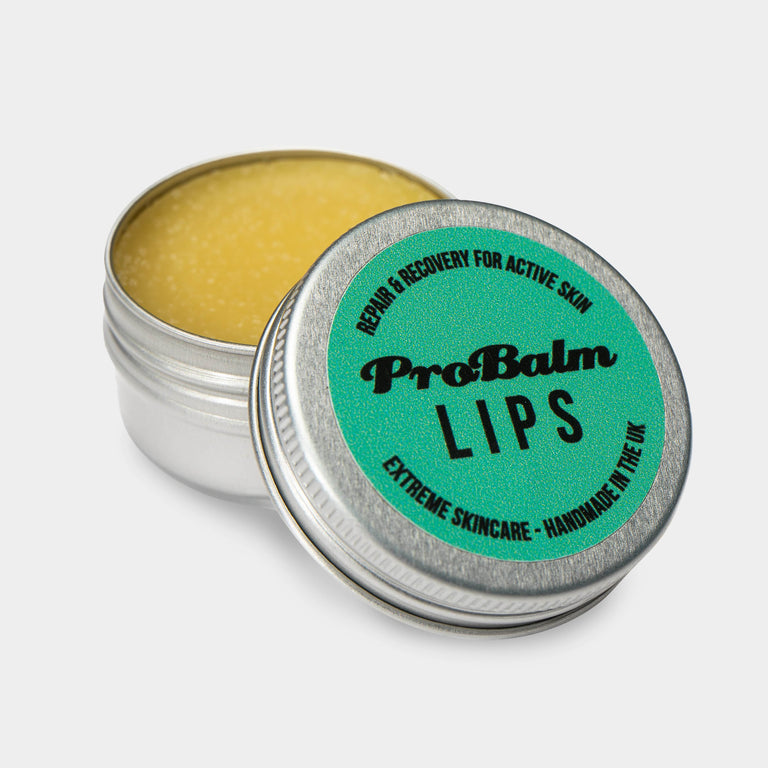

After an entire day’s effort, he could still see his last bivouac site. For two days, Jurek fought his way through the snow. Each night he examined his feet, which had become slightly frostbitten on the Dhaulagiri descent and the three nights out. Each day the blisters grew. They became infected, oozing foul-smelling pus.

He cleaned them, bandaged them, and carried on. When he reached Marpha, he stumbled into the house where he had slept on the way in to Dhaulagiri. What had seemed a wretched hovel now felt like five-star luxury. They fed him, even offered him brandy to celebrate his successful climb, and then informed him the next flight out wouldn’t leave for another three days.

The nightmare of frustration was continuing for Jurek. He had to get to Kathmandu.

The Cho Oyu permit ended on 15 February. He had another 8,000er to climb.

The following morning, he convinced a porter to compress the seven-day walk back to Pokhara into three. Off they went, the young lad carrying Jurek’s pack, and Jurek nursing his blistered feet.

When they reached the trailhead, Jurek hailed a taxi, arriving at Pokhara station as a bus was about to leave for Kathmandu.

He leapt on board and reached the city that evening at 10 p.m. He then hobbled over to the trekking agency in charge of the Cho Oyu expedition and radioed the team.