Al Humphreys' new book "Local" explores finding joy nearby. Before release, he completed one last ride for the book's final edits

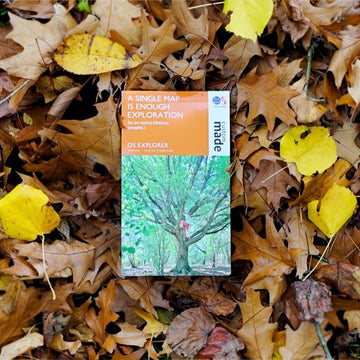

Longstanding Alpkiteer and friend of Alpkit, Al Humphreys, is releasing his new book soon. Local is about how to find joy in your nearby. Grab a cup of tea and settle in for this excerpt from Al's latest release.

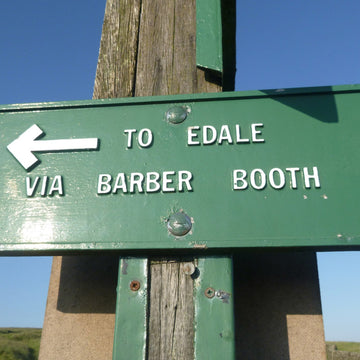

As I made the final edits to this book, there was one more ride I wanted to do before letting go of it. I decided to cycle through every square of my map in a single, unbroken journey. Starting in the middle and circling outwards through all 400 grid squares appealed to my old instinct to spiral away faster and faster until slingshotting beyond the gravitational pull of home and blasting out into the world. But I decided instead to begin on the map’s outer fringes and to circle inwards until I arrived home, or, more precisely, reached the pub. It fitted better with my search for somewhere to belong, and was a dive towards the heart of things.

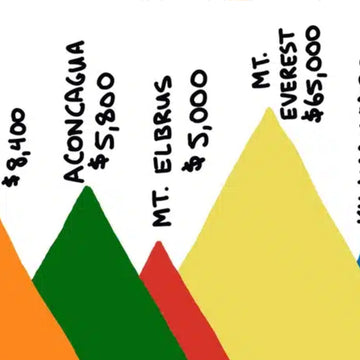

The route I plotted through every grid square was 300 miles long, climbed 5,800 metres and looked utterly ridiculous, like a plate of wiggly spaghetti. I transcribed it from my paper map into a digital navigation app to save me having to check the map at every junction. Ride with GPS worked brilliantly.

Two-thirds of it was on paved roads, the rest was byways, footpaths and the odd spot of gentle trespassing. I didn’t know where I would eat or sleep, but I was confident those details would work themselves out over the next four days. It was time for 300 miles of adventure on a twenty-kilometre map (I think in miles when I’m cycling, even on a metric map).

I felt the old combination of joy and nerves as I ate a large breakfast, squeezed a last-minute extra warm top into my pack, and hit the road. Spring was on its way as I pedalled through familiar grid squares towards the edge of my map, the roads lined with blackthorn blossom and the first blush of hawthorn leaves. This was my world: my roads, my sunshine, my plastic junk floating in the river, my broken bottles. It was my home, and I was happy to be here.

I crossed paths with a cyclist who was out from the city for a day ride. He drove buses for a living, wore designer cycling clothes and was jealous that I was going to camp out tonight.

‘I’d love to do that, but I’m too scared,’ he said, pointing at the bags on my bike. ‘I’ve camped with friends, but never on my own. I need to lose my camping cherry.’

I asked why he’d ridden out this way.

‘I like scuzzy stuff. Old, broken, weird, forgotten. That sort of stuff, you know? Scuzzy. There’s loads of it round here.’

He looked embarrassed at this odd admission, but I knew exactly how he felt.

‘Me too!’ I said. ‘Edgelands, bus depots, graffiti. Scuzzy! I love all that too.’

I certainly got my fill of scuzzy on this ride. But I also heard the first lapwings and skylarks of the season. And while riding the hard shoulder on an unavoidable but stressful stretch of dual carriageway, I spotted my first brimstone butterfly, a flash of yellow darting among the roadside litter.

Around mid-afternoon on the first day, I paused for coffee and rocky road cake in a posh village of black-and-white Tudor buildings and Teslas. I flicked idly through the Financial Times Weekend supplement that a previous customer had left behind. I was embarrassed by how knackered I already felt. All those weekly bimblings clearly hadn’t helped my endurance. Earlier, I’d rested in a rundown town that smelt of weed. A Home Office Immigration Enforcement van pulled up, sirens wailing, and the officers piled swiftly into a block of flats. I watched a street cleaner sweep a cigarette butt, miss, sweep again, miss, then shrug and walk on.

My map was actually far more rural than I had realised, more wooded and hilly, and less built-up. That was a nice realisation, but it also meant I failed to find a village pub to eat dinner in, so had to backtrack a few miles to a McDonald’s in a retail park. I whiled away a couple of hours there, merrily stuffing my face with delicious Diacetyl Tartaric Acid Ester of Mono- and Diglycerides while I charged my camera batteries and stayed warm until it was time to sleep.

I slung my hammock beneath a three-quarter moon in a wood I’d visited earlier in the year. The night was bitterly cold, and by dawn my water bottles had frozen solid. I cursed at the stupidity of shivering through a long night just a few miles from my cosy bed. At first light I pedalled quickly to the nearest petrol station to recover with hot bad coffee. I resolved to detour home later for a warmer sleeping bag and a tent.

I was weary on day two, slogging up muddy trails through woods and down slippery footpaths across fields. Heading through every grid square like this was making my map feel huge. Although I’d often felt concerned this year about the scale of new housing developments, this microadventure showed me there was enough space for everyone here, as well as for wildlife and farming.

We can certainly rewild some land for nature once people are enthused to think it’s a valuable idea. Soil can heal and hedgerows and ponds can recover once there is a demand to support sustainable, regenerative farming. The river filled with slimy lager cans is a clear chalk stream at heart, home to water crowfoot flowers and otters, and just waiting to revitalise as soon the political will is there to get it cleaned up. This is all so achievable, making it an exciting time to be an engaged adult concerned with leaving the world in a better state for our children.

Each day of my ride, the trees seemed to turn a little greener. The dawn chorus woke me earlier each morning. Winter was on its way out. Brighter days lay ahead.

‘Here we go again,’ my map said to me. ‘Another season, another lap of the sun, another lap of the map. Another chance to make the best of things and choose to bloom as brightly as you dare.’

My sinuous route wound round and round, nonsensically but pleasingly. It was astonishing how many new back roads and bridleways I found, even from just whizzing straight through grid squares. Before this year, I had focused too much on the oceans and mountains I did not have where I lived. But that had been replaced by a strong sense of how much this map did have to offer. I was proud of how much I now knew about this area. If you joined me for a ride, I could show you around well.

I passed rambling old houses with tennis courts and trampolines, the sort I will buy once I start writing blockbuster bestsellers, rather than niche books about bicycling around business parks, decaying tower blocks with washing lines and barbed wire on the roofs, and repeating suburban streets with everything in between. As I rode randomly through so many diverse lives, I hoped that contentment was spread more evenly across my map than wealth or opportunity seemed to be.

I slept well in my warm tent that night, back into the groove of the cycle touring life I knew so well. This trip was no different from all the times I’d ridden hundreds of miles in other countries, apart from the need to accept that I wasn’t moving very far, and to be OK with that.

There was a lot to love about riding a long way yet never being more than ten miles from my fridge. I loved the detours down hidden-away footpaths hemmed in with chain-link fencing around railways shunting freight goods, faceless facilities management warehouses, sewage works, and hedgerows scattered with nitrous oxide canisters.

I loved the estuary with its derelict broken windows and its birdsong and dramatic skies scudding with storm clouds, bursts of rain, and rainbows. I loved the marshes, pylons and dilapidated wrecks of boats hauled up on muddy creeks, paint fading, wood peeling, full of intrigue and character.

I loved the peaceful hideaways that few people knew about, the silent valleys and my first bluebells of the year. I loved the wild predators who made this tame landscape their home: the foxes, the marsh harriers, the dragonflies and brown trout.

I loved the ancient churches and gigantic trees standing proud from long before the industrial and agricultural revolutions, and I loved knowing that they will still be here once we get back to living in harmony with nature and our communities again. And I loved that I was free to enjoy all these places on miles of public footpaths.

I didn’t much like all the ‘Keep Out’ signs, the locked-away lakes, the litter, the dog poo bags, and the miles of new streets named after the meadows, birds and trees they had replaced. But even so, there was still plenty of space for me to watch the sun set behind a titanic oak, the golden sky splintered like a shattered windscreen by the tree’s thousands of crooked twigs and branches. As the first stars appeared, I pitched my tent in an empty wood that I shared only with a duetting pair of tawny owls.

My frustration at the start of this book about living in a built-up area felt mistargeted on this ride. It wasn’t that there were no woods to explore or trails to ride here. My real problem was having nobody to do those things with, and I hadn’t solved that problem this year. I frequented plenty of cafés and pub gardens, delighted to squander more money on cold lagers and steaming Americanos in four days than I had during four years of riding round the world on a young man’s frugal budget. I savoured the lone traveller’s prerogative of listening in anonymously from the edges, overhearing café conversations about a long-lost brother from Australia, one half of a phone argument with a boyfriend, and a place to buy excellent belly pork. There are so many lives playing out on this small map, so many demands on the land’s resources, so many differing priorities.

My meditative looping round and round the map towards its centre gave me time to think about the ways our priorities differ. Not everyone will agree with the things I care about. But if any topics in this book do resonate with you, I urge you to tell your friends about them and to write to your MP to engage them in the conversation (it is quick and easy to do via theyworkforyou.com). Nothing major changes without sufficient people speaking up, and without voters holding their officials to account.

Ultimately it is the government who will decide whether or not we meet our climate targets, whether we shift swiftly to electric vehicles and effective public transport, whether sustainable farming is adopted seriously, whether paying public money for public goods will result in cleaner rivers and an increase in rewilding and conservation, and how much importance is placed on helping people to spend more time exercising in the outdoors, with improved access and education on how to care for nature.

Dodging broken glass down a back alley on my final morning, I came across an abandoned building with only the walls still standing and old vehicles rusting among self-seeded sallow saplings. An elderly gentleman was walking his dog and I asked if he knew what the building had been.

‘A builder’s yard, I believe,’ he said. ‘It’s been abandoned as long as I’ve known it though. Forty-odd years since I moved into the area.’

‘Where did you come here from?’ I asked.

‘Only from town, just a couple of miles, you know. I don’t know about you, but I’m not exactly a world traveller.’

‘You must like it here to have stayed so long?’

‘It’s all right, mate. But they’ve built all those new homes on the old community field. Barry used to keep those pitches immaculate, you know. I can’t believe they squashed so many houses on there. Sometimes I think it’s time to move on. But there’s all the upheaval. And it’s what you know, right? People get used to a place. It’s home, isn’t it?

I had pedalled, pushed and carried my bike for four days, going round and round my map. I fixed punctures and lifted the bike over gates. I took selfies and wrong turns. I fell off, hard, and stuck my middle finger up at the passing car taking a photo of me as I lay in pain on the pavement. I ate cakes and crisps and croissants and curry. I rode through hundreds of grid squares. But in the end, I didn’t manage to ride through every square.

I had overestimated how far my unfit legs could carry me each day, and underestimated how much I like cafés these days. So I ran out of time before my family returned from a trip away. I turned for home and pedalled back to them (via the merest of stop-offs in a pub garden to toast the end of this long project).

Even after a year plus four days, I still hadn’t covered many of my map’s roads and footpaths. There were still grid squares I had to label as terra incognita. But I feel content knowing they are out there waiting for me to explore in the years ahead.

My small weekly forays had been a contrast to the bigger adventures from my past. Long, slow journeys through unfamiliar landscapes and cultures are an astonishing privilege, stuffed with lifelong lessons and perspectives. Let nothing discourage you from heaving on a rucksack or strapping a tent to a bike and leaving town. Go! You can’t beat that feeling of being untethered and free. Do it if you possibly can. Those star-filled nights, huge horizons, and strangers who will become friends: they are out there waiting for you, your life lying before you like a blank page, brilliant with possibility, daring you to begin.

Yet Thoreau, whose dogged enthusiasm for staying put and paying attention makes him the unofficial ambassador for this book, boasted that he had ‘travelled a good deal in Concord’, his small home town in Massachusetts. I like that idea too. For if I were to boast in my local pub, pint in hand, I could certainly bore punters with memories of cycling through Albania and Zimbabwe, or paddling to Barbados or through the Yukon. But I would now also tell them, with fair confidence that nobody else knew these places, about a delicious chalk stream under a motorway bridge near here, a hilltop of summer orchids and oregano, and a twisted oak tree, six metres round and centuries old, standing dark and strong in fields of snow.

I am proud to know these familiar little spots, for they have helped me learn to appreciate where I live and feel more attached to it, despite Thoreau’s insistence that a landscape can ‘never become quite familiar to you’, no matter how long you live there.

But can a single map really be enough exploration for a lifetime? Pootling around one map for a year rarely felt like an adventure, I’ll admit. But it did often feel like exploring. I enjoyed many tingles of surprise on my map of small wonders. I won’t push your credulity in claiming it was epic, but something about the experience resonated with the sliver of my soul that wants always to look beyond the horizon. My weekly meanderings did a decent job of keeping a lid on that restlessness. So much so, in fact, that I feel something akin to vertigo at contemplating the prospect of having the entire globe to explore.

If you pick up a map of your local area, choose a grid square at random, and begin walking around it with your eyes open, you’ll soon be mesmerised by the possibilities for local exploration. After that, it is up to you. What will you look for? What will you care about and want to take a stand on? (When you start exploring your own local map, please tag your photos on social media with #ASingleMap to help inspire others.)

My map has changed my perception of home, made me less tempted to fly, and more motivated to care for the environment. There is so much potential for a future full of positive stories, if only we demand change and take action.

This local map could fuel my curiosity for ever, in a way I once thought only distant places could do. My map is a fractal of the world. Today is a fractal of my life. To know one place well and to make it better is the work of a lifetime. And so, yes, a single map can be enough.