Wild Waters by Susanne Masters: Embracing the beauty of wild swimming.

You're reading an extract from Wild Waters by Susanne Masters.

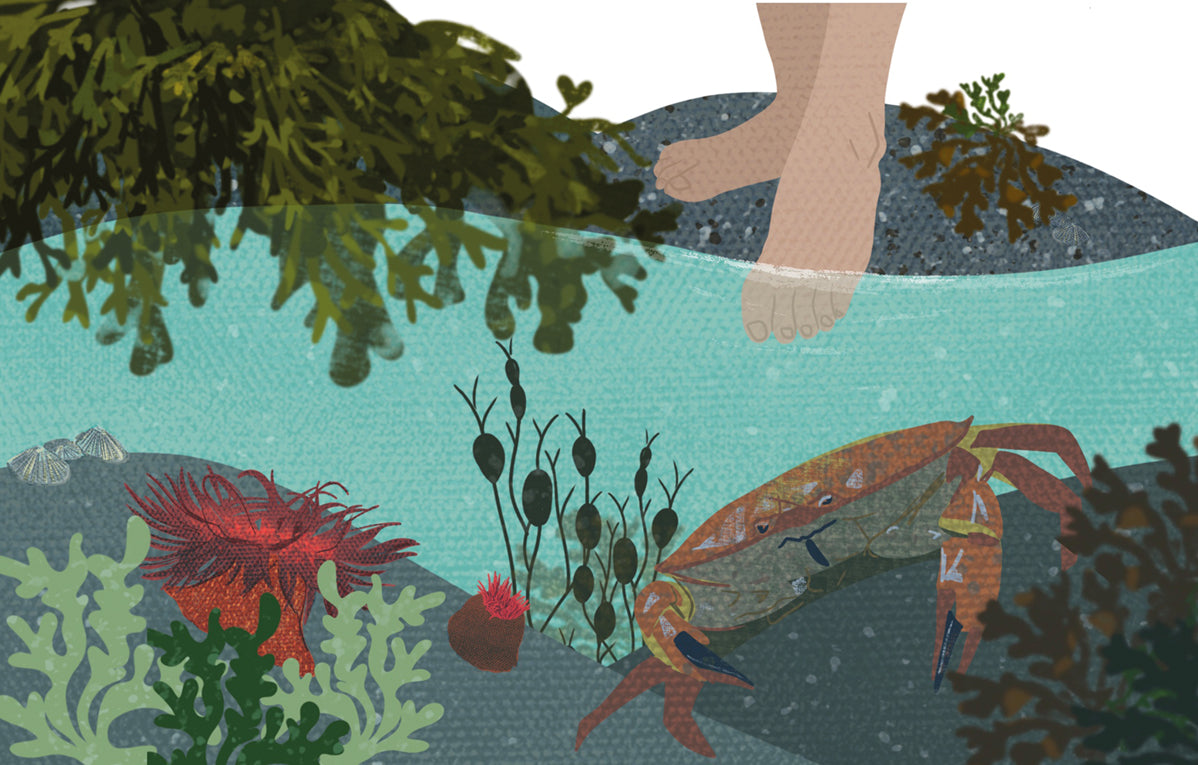

"Life isn’t spread homogenously across our planet. Even within the realm of wildlife associated with water, a range of influences – geology, topography, salinity and human activity – combine and create habitats that some but not all species can live in. The wildlife we see tells us about these influences that are often invisible to the passing or naked eye. Wildlife is a cast of characters that informs us about places we are in.

The River Thames illustrates how habitats change over the course of a river, and under different influences. It is hard to imagine the clear-running stream slipping between trees in a Gloucestershire meadow as the same entity as the broad and brackish expanse of water between the Houses of Parliament and the South Bank. In the upper reaches, small chub (Squalius cephalus) hang in shoals of silver; in the lower reaches, sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) spawn. Chub don’t have sea lamprey – also known as vampire fish – sucking their blood because sea lamprey only enter rivers with very clean water to spawn. Sea lampreys otherwise live and dine at sea, and chub stay in freshwater, so their habitat preferences keep them separate.

In 1957 the Thames was declared biologically dead. Its water was so low in oxygen that few species could survive in its anaerobic condition. Between its pure spring water start in Gloucestershire and emptying into the North Sea, the river was corrupted. A particularly sullen stretch of the Thames extended for a couple of miles either side of London Bridge, where the city and its people combined with damaged infrastructure were a problem. Victorian sewers that had been destroyed during Second World War bombings had not been replaced.

Standing on London Bridge now and looking down, the Thames water still looks murky brown. But it’s a healthy shade of colour caused by particles stirred up in tidal sway. Rare but increasing sightings of seals in the Thames as it runs through the centre of London tell us that, unseen by most people, fish are swimming in the river and there are enough of them for a seal’s appetite. The Zoological Society of London monitors fish in the Thames, and in 2016 found twenty-one smelt (Osmerus eperlanus) eggs at Wandsworth Bridge. The fact that these fish, notable for smelling like cucumber, were returning to spawn in the Thames was considered a marker of how much its water quality had improved.

Bringing the Thames back from the dead wasn’t done just by sorting out London’s sewers; wartime had put a strain on all our rivers and it took national effort to bring them back to life. During a session in the House of Lords in 1959, Pollution of Rivers and Estuaries was discussed. Fortunately, not everyone in the House of Lords or the House of Commons, who had previously discussed a bill on Clean Rivers (Estuaries and Tidal Waters), took the view of Viscount Simon, who inherited his peerage and power from his father. Viscount Simon stated, ‘The natural channels for the disposal of waste in a country like ours are undoubtedly our rivers. People sometimes say (and I believe that this has been mentioned this afternoon) that this or that river is like an open drain. In my view, that is exactly what a river ought to be.’ He continued to expound the view that rivers should be a clean and healthy drain, not a foul one, and in fact operate like man-made sewage disposal plants in terms of bacteria breaking down organic waste in the presence of oxygen. He bemoaned the overloading of rivers as natural sewage disposal systems, but did not think it necessary to purify sewage 100 per cent, as the river would deal with it. He commented, ‘I do not want to go into technical details, and indeed I am incapable of doing so.’ Fortunately for the majority of the population, who do not have hereditary power and have not scaled political heights, other members of the House of Lords were concerned about their fishing and did not agree with Viscount Simon. Lord Balfour of Inchyre, a keen fisherman, cited stakeholders including 2 million fishermen and said, ‘Many of your Lordships have first-hand knowledge around the country of how fisheries and oyster beds are being poisoned’. He named other stakeholders, including residents and holidaymakers, who were entitled to better conditions, and reported that ninety per cent of cattle were drinking sewage-polluted water. He gave thanks to the kidneys of the cattle for their noble work in absorbing pollution and stated, ‘sport, industry, amenities and health – the community are not getting the purity to which they are entitled’.

Various Lords gave examples of rivers in their holdings that were polluted, including an outbreak of typhoid because people had eaten shellfish from the Clyde estuary. In addition to sewage release, agricultural pollution via chemicals applied to crop fields, earth released by washing crops and ‘synthetic detergents which are poured down sinks by so many housewives all over the country’ were blamed for the state of our rivers. The Lords were well aware that river pollution was a recurrent issue, having previously been the topic of sixteen Acts of Parliament and fifty-four reports and investigations.

Clearly the House of Lords deplored the state of our rivers. The value of rivers was a matter of the economic cost of pollution and the fact that people were entitled to clean water. If fish were dead in the water, it was a sign that the water was not suitable for children to bathe in. Wildlife was absent from consideration, and so was any concept of a duty of custodianship and the idea of reciprocity – that natural resources are given to us but we also carry responsibility for them.

Since 1857, when the Thames Conservancy, the first public body established to prevent river pollution, was created, successive sets of legislation have responded to pollution because it affects our lives. The Industrial Revolution and emergence of polluting industries on a vast scale led to the introduction of legal obligations for manufacturers to treat and dispose of waste water without contaminating rivers.

Innovation reduced some pollution by driving market forces in different directions. For example, the advent of digital photography caused a downturn in photo printing, and this reduced the release of silver particles used in photo development into freshwater. Industrial chicken factories have attracted attention for leaching excessive nitrogen into rivers, which causes algal blooms, reduces oxygen levels in water and kills wildlife. There are established means of dealing with manure that can be applied to deal with waste from chicken-rearing and egg-producing factories, and consumers can make choices on eating less chicken and selecting the conditions in which their chicken is reared. But as a whole, our society and its mechanisms of legal constraints remain orientated towards defending resources to ensure that we can use them. What happens if we change our view from entitled and transactional – on the basis of benefits we receive – to seeing wild waters as diverse inhabited places where we behave as guests who would like a return invitation?

![Straven [Womens]](http://alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/womens-straven-2025-1.jpg?v=1744723504&width=768)

![Straven [Womens]](http://alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/womens-straven-2025-3.jpg?v=1744723500&width=768)

![Tarka Wetsuit [Mens]](http://alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/mens-tarka-2025-1.jpg?v=1744723498&width=768)

![Tarka Wetsuit [Mens]](http://alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/mens-tarka-2025-4.jpg?v=1744730706&width=768)

![Tarka Wetsuit [Womens]](http://alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/womens-tarka-2025-1.jpg?v=1744723496&width=768)

![Tarka Wetsuit [Womens]](http://alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/womens-tarka-2025-3.jpg?v=1744730715&width=768)

![Terrapin Natural Swimming Wetsuit [Mens]](http://alpkit.com/cdn/shop/products/mens-terrapin-e.jpg?v=1695745450&width=768)

![Silvertip Cold Water Wetsuit [Womens]](http://alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/silvertip-womens.jpg?v=1706614008&width=768)

![Silvertip Cold Water Wetsuit [Womens]](http://alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/SWAKSILTSC-neoprene-outdoor-swimming-cap-in-water_758f3933-2d1a-471a-a965-24105416e9b2.jpg?v=1706614013&width=768)

![Element Wetsuit Jacket [Mens]](http://alpkit.com/cdn/shop/products/element-mens-jacket-pants-ecom-2.jpg?v=1695902047&width=768)

![Element Wetsuit Vest [Mens]](http://alpkit.com/cdn/shop/products/element-mens-vest-shorts-ecom-2_bed513c4-b564-4446-856d-d889f90f885e.jpg?v=1695902060&width=768)

![Element Wetsuit Pants [Mens]](http://alpkit.com/cdn/shop/products/element-mens-jacket-pants-ecom-2_38dbf092-f607-4bbd-bd7a-0477da29bcef.jpg?v=1695902051&width=768)

![Element Wetsuit Shorts [Mens]](http://alpkit.com/cdn/shop/products/element-mens-vest-shorts-ecom-2.jpg?v=1695902057&width=768)

![Element Wetsuit Shorts [Womens]](http://alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/womens-element-shorts.jpg?v=1702653059&width=768)

![Element Wetsuit Shorts [Womens]](http://alpkit.com/cdn/shop/products/element-womens-vest-shorts-ecom-1.jpg?v=1702653054&width=768)